ILLINOIS MUSLIMS:

NEEDS, ASSETS, AND OPPORTUNITIES

JULY 28, 2022 | BY DALIA MOGAHED, DR. JOSEPH HOERETH, OJUS KHANOLKAR, AND UMAIR TARBHAI

RESULTS: INDIVIDUAL

Survey questions pertaining to the individual included a broad range of topics: identity, health, food access, volunteering, and faith-based giving. Our analysis focused on identifying assets and needs, which we discuss below.

ASSET: Strong Faith Identity

Muslim respondents in our study identified strongly with their faith. Around 84% of Muslim respondents stated their faith was very important to their self-perception, compared with 39% of the Illinois general public respondents. Previous research shows that a stronger faith identity among Muslims is linked with a stronger national identity. In fact, in a study from 2016, 91% of Muslims who stated they had a strong faith identity also had a strong American identity, while only 68% with a weak faith identity identified strongly with being American [7]. Previous research has also suggested that faith can act as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes.

While faith was a strong identifying factor, focus group participants were quite varied with regard to how they talked about their identities. Some describe multiple national identities, including American, a country of origin if they were immigrants as well as an ethnicity in combination with the other two identities. Notions of what it means to be American were complex as well. For example, the identity of what some might describe as the proud immigrant was discussed, where one might say living in America and being American is a privilege with specific rights and responsibilities. Yet, another view on identity heard in the focus groups was a bit mixed. It is that of a Muslim who is American but believes that being a Muslim in America requires one to acknowledge America’s history of injustice and present-day inequities while also committing to confronting those inequities.

“For me being American is having the rights and freedoms of each and every American that makes us feel we are Americans, if we have rights and freedom just like everyone else.” – Muslim resident of Illinois, 24

In a focus group with African American participants, the sense was that faith is inextricably a part of their self-identity to such an extent that questions about their race separate from their faith do not align with how they see themselves. Being Muslim is a part of being Black for them and vice versa.

“When we make a conscious decision to follow the tenets of Islam, we become formally Muslim. But beyond the African American tradition, we are Muslim by nature.” – African American respondent, 72, Chicago South Side

NEED: More Halal Options

With this finding, however, it should be noted that there also need to be systems in place to support their faith needs. Specifically, 94% of Muslims stated it is ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ important that their purchase decisions be halal (74% stated it was very important, and 20% stated it was somewhat important). Yet, 39% of Muslim respondents with school-age children and 32% of students enrolled in college said they didn’t have access to halal food at their school. In contrast, around 48% of respondents in the Illinois general public sample stated their faith was an important factor in their purchase decisions. One quarter of Illinois general public respondents with school-age children (24%) and none of the college students reported not having access to food that met their religious dietary restrictions at their school. This is, of course, not surprising as the majority of the general public do not have religious dietary restrictions.

A bar graph showing the percent of Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who lack access to food that meets religious dietary restrictions in school settings

Focus group participants reinforced the importance of observing halal or at least trying to eat halal. Some indicated they or someone in their network may drive great distances to access halal food. However, they note that it is becoming increasingly more accessible.

“We drive to Peoria, St. Louis, Champaign, Chicago to get halal. Now, the big stores carry halal meat. …Walmart has halal meat. Meijer is also starting to carry halal meat. [I’m] buying up the lamb they had and I’ve started seeing the halal mark on it. We are starting to see more international things in grocery stores because we have a big population.” – African American respondent, 57, Springfield, Illinois

NEED: Access to Appropriate Healthcare

While Muslim respondents reported needing immediate care less often than did those in the state’s general public when they did need care, Muslims in our survey had a harder time getting it. One-fifth (21%) of Muslim respondents said they needed immediate care in the last 12 months, but 25% of those who needed care stated they ‘sometimes ‘or ‘never’ got care as soon as they needed it. In comparison, around 30% of the Illinois general public sample stated they needed immediate medical care right away in the past 12 months, and around 13% of those individuals stated they ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’ got care as soon as they needed it. That means Muslims in our sample who needed care right away were twice as likely as the general public to sometimes or never get it (25% vs. 13%, respectively).

Future research is needed to assess what factors explain this result, and how much, if at all, implicit bias may play a role in Muslims’ greater likelihood to report difficulty receiving timely healthcare. According to ISPU’s 2020 national survey of American Muslims, roughly a third of Muslims who reported experiencing religious discrimination said it occurred while seeking healthcare.

A bar graph showing the frequency of getting medical care when needed among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

NEED: Affordable, Culturally Appropriate Mental Health Services

The need for support extends to mental health. In the year prior to the survey, half of survey respondents, both Muslim and the general public, experienced some sort of mental illness symptom (47% and 51%, respectively). These symptoms included anxiety, sadness, and loss of joy. While the pandemic and its stressful effect on so many individuals may explain some of this, it is a longer term challenge, as 53% of the Muslim sample and 56% of the Illinois general public sample reported they had experienced mental health symptoms at some point in their life. Most respondents who reported experiencing mental illness symptoms at some point in their life also reported experiencing them in the past year.

However, despite similar rates of reported negative mental health symptoms, Muslim respondents are less likely than their Illinois general public counterparts to seek treatment. Thirteen percent of the Muslim sample sought help from a licensed therapist in the year prior to the survey, as opposed to 24% of the Illinois general public. When asked about reasons for reluctance in seeking treatment, among respondents in the Illinois Muslim sample who reported symptoms of mental illness but did not seek treatment, 35% reported that it would be too expensive, 11% said they didn’t trust mental health professionals, and 10% said they would feel embarrassed. This finding indicates that more affordable mental health services are a significant need within the Muslim population.

The survey also asked respondents if they have ever attempted to take their own life. Among the Muslim sample, 8% reported attempting suicide. While lower than the 18% of individuals in the Illinois general public sample who report the same, any number is too high, and these findings reiterate the significant need for culturally appropriate and affordable mental health services for the Illinois Muslim community.

A bar graph that shows the barriers to accessing mental health treatment reported by Illinois Muslim respondents who have not sought treatment from a mental health profession and reported symptoms of mental illness

In exploring these findings further, focus group participants identified mental health support as a critical need within the community, specifically indicating they feel that such services need to be more accessible. Participants also consistently mentioned a very strong stigma, although not always using the word “stigma,” identifying a negative association or perception of mental health within the community. Some participants indicated that mental health issues are sometimes perceived as a result of individual behavior or failure to do something, as if the individual is being blamed for causing the mental health condition. This notion of “self-blame” or “blaming the victim” sentiment discourages individuals from seeking help when they need it, regardless of whether that help comes from within the community. The main point of their comments was that efforts should be made within the Illinois Muslim community to reduce or address this stigma.

“I think the public, we are not good at dealing with mental health. The only hope is within ourselves. You can share with a friend and that person can help you in cases of stigma. A friend you can talk to personally. I need a friend who is a Muslim like me who can understand and get whatever I’m talking to him or her about.” – African American Illinois resident, age 24

“It may just be my own impression, but mental health isn’t something talked about. If anyone has it they are told to do what needs to be done but don’t dare talk about it or share your experiences. It’s a mix of both peer pressure and clearly stated. People have said ‘if that’s something you’re dealing with, you can go talk to someone, but you don’t have to say that to bring everyone else down.’” – Illinois resident of South Asian origin, age 20

RESULTS: FAMILY

The survey included questions about the needs and assets of the family and the household unit. Questions pertaining to family touched on topics such as marriage and divorce, care for extended family, access to jobs, and household expenses.

ASSET: Muslim Marriage

In terms of family makeup, 63% of the Muslim sample responded that they were married at the time of the survey while 39% of the Illinois general public sample reported the same. Though simply being married is no guarantee for a thriving and healthy family, marriage is still a foundation for healthy family units which extensive research suggests are linked to better outcomes for children.

A bar graph showing marital status of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

ASSET: Strong Inter-generational Support

Compared to the Illinois general population sample, a greater percentage of the Illinois Muslim Sample care for their elderly relatives (29% vs. 21%, respectively), suggesting the elderly in the Muslim community are more likely to have family engagement and companionship, which research suggests contributes to better mental and physical health outcomes.

NEED: More Support for Divorced Families

Despite only eleven percent of Muslim respondents saying they have ever been divorced, 91% of Muslim respondents agreed that their faith community should be more supportive of divorced families. This can include divorced and separated families as well as those going through divorce. This presents an important opportunity for community organizations, Muslim-run counseling and support organizations, as well as houses of faith, to advocate for more resources devoted to support programs for divorcees. By contrast, 74% of Illinois general public respondents said they believe their house of worship needs to do more to accommodate divorcees.

A bar graph showing level of agreement with the statement: “My faith community should be more supportive of divorced people” among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

Reasons for Divorce Common Across Communities

Of those in the Illinois general public sample and the Muslim sample who responded that they have ever been divorced, the reasons given are very similar across both samples. The most common reason for divorce was cited as infidelity, listed by 30% of Muslim respondents and 27% of Illinois general public respondents. The next most commonly cited reason within the Muslim sample was incompatible goals, stated by 16% of our Muslim respondents, compared with 8% of the Illinois general public sample. For the Illinois general public, an equally important reason for divorce were conflicts over money and finances, which 10% of the Illinois general public sample cited. In comparison, 6% of the Muslim population cited financial conflicts as a reason for divorce.

NEED: Greater Education and Support for Domestic Violence Survivors

Muslim respondents face similar rates of domestic violence as the Illinois general public respondents. Among Muslim respondents, 17% stated they know someone in their faith community who has been a victim of domestic violence, on par with the 14% of Illinois general public respondents who stated the same. Conversely, Muslim respondents were less likely to report these transgressions to either law enforcement or a community leader. Among those who knew a victim of domestic violence, 35% of Muslim respondents stated that the individual reported the transgression to a member of law enforcement while 58% of Illinois general public sample responded the same. Similarly, 31% of Muslims in the Illinois sample who knew someone in their faith community that was a victim of domestic violence stated that the individual reported the violence to a community leader while 53% of the Illinois general public responded the same.

This differs from ISPU’s American Muslim Poll 2017 findings on American Muslims in which it was found that 54% of Muslims who knew someone in their community who was a victim of domestic violence reported the transgression to law enforcement and 51% reported the transgression to a faith leader.

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who know someone who reported domestic violence cases to law enforcement and/or faith community leaders

NEED: Sandwich Generation Common

Among the Illinois Muslim sample, as stated earlier, 29% reported that they are currently caring for an older family member (either a grandparent or a parent), compared with 21% of the Illinois general public respondents. Of those who stated they are caring for an elderly member of their family, 91% reported that they help out with hands-on work, including 8% providing help with errands and housework, 34% with transportation, 32% with health-related tasks (such as monitoring blood pressure or blood sugar), and 17% acting as a main social outlet. A greater proportion of the Illinois general public sample reported supporting their parents financially (37% of the Illinois general public vs. 9% of Illinois Muslims). This suggests that many Muslims in Illinois are taxed with caring for parents and children at the same time in ways that make demands on their time, not just their finances, pointing to a need in the community for elderly care support. Further research is recommended to understand the impact of this added mental and emotional labor on Muslim mental health.

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who help a parent or grandparent with various tasks

NEED: Improved Access and Awareness of Job Placement Opportunities and Social Services

When comparing the financial health of the Muslim community sample to the Illinois general public, we found that the Muslim sample respondents struggled with job loss on par with the those in the Illinois general public (30% in both samples). This is an area where social service organizations of all kinds can concentrate resources. In addition, 22% of Muslim respondents have been laid off, as have 21% of Illinois general public respondents. Unsurprisingly, significant shares of the Muslim and general public sample report worrying about paying the bills—33% of Muslim respondents and 46% of our Illinois general public respondents—pointing to a need in Illinois across communities.

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public that are worried about being able to pay their bills

Further, 28% of our Muslim respondents stated they have accessed social welfare programs like SNAP/TANFF, compared with 35% of the Illinois general public respondents. Respondents in the Illinois Muslim sample were less likely to struggle with food insecurity in the past year. That being said, it is still important to note that 14% of Muslim respondents in our sample have struggled with food insecurity, which can be addressed by increasing knowledge about accessing social services. By comparison, 38% of the Illinois general public sample stated they faced food insecurity. The Muslim sample is more likely to be married and less likely to be separated or divorced and, therefore, part of a family unit, which may explain why the economic impact of job loss is less severe. Since our sample likely skews wealthy, the actual share of the Muslim population that is food insecure is likely higher, especially considering that nationally representative figures show that a third of Muslims in the US are low income, the largest share of any faith or non-faith community. Any amount of food insecurity is a need in any community and may be partially addressed by educating those in need about available social services.

A bar graph showing the percentage of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who have accessed social welfare programs

RESULTS: COMMUNITY

Topics covered by assets and needs in this section pertained to questions about the Muslim community in Illinois. This included questions about giving to Muslim organizations; mosque attendance; support for health and social services; inclusivity in mosque decision-making; and discrimination within and toward the Muslim community.

ASSET: Illinois Muslims Give Generously

Another asset found within the sample of Muslim respondents is a willingness to contribute to their community. Around four out of five Muslims have donated to an organization associated with their faith community in the last 12 months. This is compared with just half of the Illinois general public sample.

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public that donate to community organizations

While roughly a third of both the Muslim sample and the Illinois general public sample contributed between $100 and $500 annually, the Muslim sample was more likely to give at the higher end of the spectrum. Roughly a quarter of the Muslim sample contributed between $1,000 and $5,000 annually compared to 16% of the Illinois general public sample.

A bar graph showing the distribution of household income among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

ASSET: Frequent Mosque Attendance Is an Asset for Community Mobilization and Mental Health

Around 72% of the Muslim sample attended their mosque at least once a month prior to the pandemic. This has important ramifications for community building. Higher mosque attendance is linked with increased volunteering and higher civic engagement for the group.⁸ In addition, more frequent mosque attendance is linked to better mental health outcomes, such as lower sadness and anger.⁹ By way of comparison, around 47% of the Illinois general public sample attends a house of worship once a month.

A bar graph showing frequency of attendance at house of prayer among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

ASSET: Muslim Community Reports Less Drug Use but Favors More Support for Addiction Care

Muslims report consuming significantly less alcohol than the Illinois general public. Of the Muslim sample, 95% stated they do not consume any alcohol as opposed to 48% of the Illinois general public sample. One-third of the Muslim sample indicated they know an individual within their faith community who has struggled with addiction, compared to 41% of individuals in the Illinois general public sample.

A bar graph showing alcohol consumption among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

However, 75% of the Muslim respondents stated their faith community needs to do more work to support individuals with addictions. This is an important asset within the Muslim community as it shows a deep level of empathy for their fellow community members and presents an opportunity for organizations and leaders in this field to gain momentum. In contrast, 53% of the general public indicated their faith community should do more to support individuals struggling with addiction.

A bar graph showing opinions about the level of support the faith community should provide to those struggling with addiction among Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

NEED: Greater Investment in Nontraditional Nonprofits

We found that while 80% of Muslims do donate to nonprofit organizations, just 3% donate to family and youth organizations or research organizations associated with their faith community while 9% give to “civic” or civil rights organizations. A lack of funding to these organizations may leave the community with less capacity to inform and advocate for their needs with policymakers. This points to a need within the Illinois Muslim community to invest in all such organizations.

Of those who donated to a faith-based community organization, 30% of Muslim respondents stated they had given to an overseas organization while around 28% of respondents said they had given to their house of worship. This compares to 15% of the general public who donated to an overseas relief organization and 41% who donated to their house of prayer.

While Muslim respondents were more likely than the general public in Illinois to support overseas relief, they were equally likely to support domestic relief organization (20% and 17%, respectively).

A bar graph showing recipients of community giving among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

These results depart slightly from trends in the nation as a whole where Muslims were found to be as likely as other faith communities in the US to donate to overseas relief.

NEED: More Responsive Muslim Sacred Spaces

Among respondents who attended their house of prayer at least once a month, Muslim respondents were twice as likely as the Illinois general public to state that their opinion doesn’t matter in their house of prayer (28% of the Muslims sample vs. 14% of the Illinois general public sample). That being said, 72% of Muslim respondents said that their opinion does count in their house of prayer as did 86% of the Illinois general public respondents. This presents a need for mosque leadership to better engage those who attend their institution and find ways to better listen and address their needs.

A bar graph showing level of agreement with the statement “In my house of prayer, my opinions seem to count” among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

There is little difference within the Muslim sample along gender lines with 26% of men and 30% of women stating their opinion doesn’t matter in their house of prayer. When examined more closely and looking specifically at the role of women in decision-making within the mosque, 25% of Muslim respondents stated they don’t believe that women are included in decision-making in their house of faith. This number is significantly higher than the Illinois general public sample, where 10% of respondents stated they don’t believe women are included in decision-making in their house of faith. Within the Muslim sample that responded to the question, 22% of men stated they believed women were not included in decision-making while 34% of women stated they believed they weren’t included in decision-making.

A bar graph showing the level of agreement with the statement “In my house of prayer, my opinions seem to count” among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

When examined along lines of race, 37% of Black Muslim respondents and 30% of both Arab Muslim respondents and Asian Muslim respondents agreed that their opinion does not count in their house of prayer while only 10% percent of white Muslims said the same. When looking across age demographics, almost 34% of Muslim respondents stated they believed young people were not included in decision-making in their house of prayer; this consisted of 37% of young adults aged 18-29, 30% of individuals aged 30-49, and 27% of individuals aged 50+. By contrast, 20% of the Illinois general public sample believed that young people are not included in decision-making in their house of prayer.

A bar graph showing the level of agreement with the statement “In my house of prayer, young adults are included in decision making” among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

NEED: Gender Discrimination

The proportion of Muslim respondents in our sample that face gender discrimination outside their faith community is similar to the proportion of respondents that face gender discrimination inside their faith community. Among the Illinois Muslim sample, 28% stated they experience gender discrimination within their faith community and 34% of Muslim respondents stated they experience discrimination outside their faith community.

A bar graph showing frequency of gender discrimination occurring from within and outside of faith community among the Illinois Muslim sample

Not surprisingly, this issue affects Muslim women much more than it affects Muslim men. While 14% of Muslim men in our sample reported experiencing gender discrimination within their faith community, 47% of Muslim women in our sample reported experiencing discrimination within their faith community. When compared to gender discrimination faced outside the faith community, 23% of Muslim men in our sample said they face discrimination, as opposed to 49% of the Muslim women in our sample who said they face gender discrimination. So, in our sample, Muslim women were roughly as likely to report gender discrimination from outside their faith community as inside.

A bar graph showing the frequency of gender discrimination by someone inside faith community among women in the Illinois Muslim sample and women in the Illinois general public

In comparison, 25% of women in the Illinois general public sample reported facing gender discrimination from within their faith community while 31% reported facing gender discrimination from outside their faith community.

A bar graph showing frequency of gender discrimination by someone outside faith community among women in the Illinois Muslim sample and women in Illinois general public

NEED: Anti-Black Racial Discrimination Inside and Outside Muslim Community

Muslim respondents also reported facing more racial discrimination outside their faith community than inside. While 28% of Muslim respondents stated they experienced racial discrimination within their faith group, 51% of Muslim respondents stated they experienced racial discrimination outside their faith group. Within the faith community, Black Muslims face the most discrimination (51%), followed by Arab Muslims (28%), Asian Muslims (30%), and white Muslims (10%).

A bar graph showing frequency of experiencing racial discrimination by someone inside faith community by race among Illinois Muslim sample

Outside the faith community, Black Muslims still face high levels of racial discrimination (59%), on par with Arab Muslims (59%) and Asian Muslims (58%). About one in five white Muslims (19%) report facing racial discrimination outside their faith community. This presents a clear need to address intra-Muslim racism, particularly anti-Black racism, as well as racism in wider society.

A bar graph showing frequency of experiencing racial discrimination by someone outside faith community by race among Illinois Muslim sample

RESULTS: BROADER SOCIETY

Survey respondents were asked questions regarding the contributions of the Muslim community to the broader society, such as economic and civic contributions as well as questions about policy priorities. Related questions included topics such as business ownership and job creation; sectoral employment; civic engagement activities; policy priorities and concerns; and external religious discrimination.

ASSET: Illinois Muslims Create Jobs

Around 12% of Muslim respondents identify as self-employed, compared with 7% of Illinois general public respondents. As part of our survey, we asked people who reported being self-employed or owning a business how many people they employed. By using this data and projecting to the entire population of Illinois Muslim adults [10], estimated to be 220,000, we find that Muslims in Illinois create more than 350,000 jobs–that’s nearly 6% of all jobs in Illinois while Muslims make up only 2.8% of the population. However, it is also important to note that 20% of Muslims in our sample are unemployed, which presents a need.

A bar graph showing employment status among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

ASSET: Diverse Expertise

In terms of type of work, one-fifth of the of the Muslim sample (21%) reported they work in healthcare. Eleven percent stated they work in each of the following categories: Education, Business, and Technology (that wasn’t engineering). In addition, around 50% of Muslim respondents reported that they had an annual income that was greater than $100k before taxes. Twenty percent made between $25k and $50k, and around 31% of respondents made between $50k and $100k. In the Illinois general public sample, by comparison, 21% made below $25k, 27% made between $25 and $50k, and 16% made above $100k. This discrepancy in income was also reflected in the rates at which social welfare programs were accessed in the Muslim sample vs. the Illinois general public sample. ISPU national surveys show that roughly 35% of Muslims make $30,000 or less while 18% make $100K or more, suggesting our sample overrepresents the rich and underrepresents the poor. We took this into account as we analyzed the data and addressed it in our focus groups.

A bar graph showing work sector represented among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

ASSET: Strong Civic and Political Engagement

Roughly nine in 10 Muslims (92%) are eligible to vote, which is similar to the Illinois general public sample (98%). Ninety-one percent are registered or planning to register with 75% of respondents registered and 16% planning to register. In comparison, 92% of the Illinois general public sample are registered to vote and 6% intend to register. The demographic among the Illinois Muslim sample that plans to register (16%) is an important opportunity for civic organizations to increase voter turnout within the Muslim population in Illinois, especially with the upcoming elections.

However, despite having a lower voter registration rate, the Muslim sample showed slightly higher rates of deeper civic engagement, such as volunteering, compared to the Illinois general public. About a quarter (23%) of Muslim respondents have volunteered for a political candidate in the past 12 months alone, compared to 17% of Illinois general public respondents.

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who have volunteered or done community organizing in the past 12 months for a political organization or candidate

Moreover, about a third (32%) of Muslim respondents have volunteered for a political candidate at some point in their lives, compared with 24% of Illinois general public respondents. This engagement extends to communication with elected officials even after the election is over. Roughly 30% of Muslim respondents stated they have contacted their federal elected officials, and the same report contacting their local elected officials in the last year. This is similar to the general public where 23% and 25% of Illinois general public respondents, respectively, said the same. This trend is seen nationally as well; nationally, Muslims are more likely to attend town hall meetings (22%), compared with Jews or Catholics (both at 18%) [11].

A bar graph showing the proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who have ever volunteered or done community organizing for a political organization or candidate

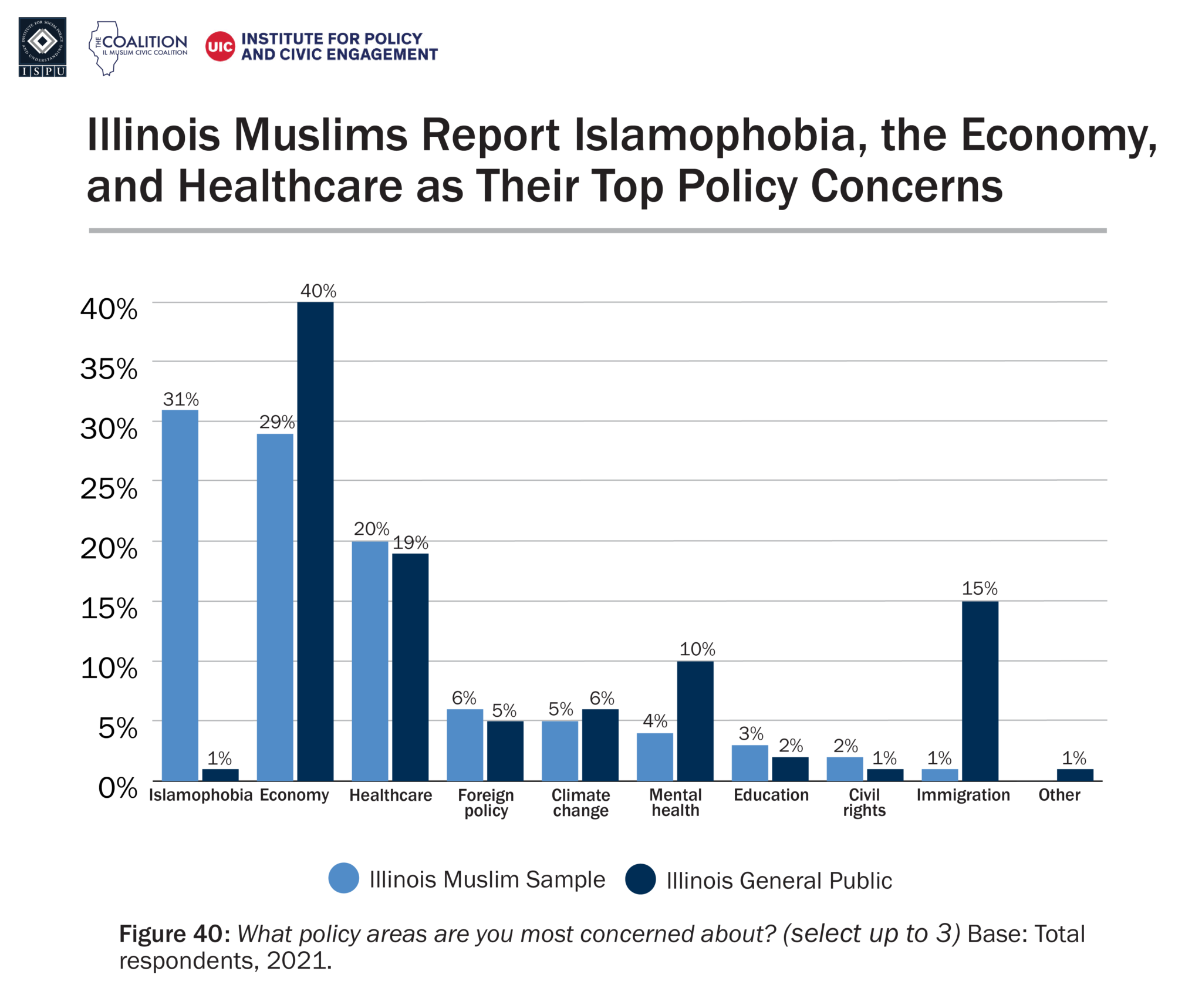

Muslim respondents shared similar policy priorities as the general public, with some unique differences. These priorities are important for elected officials to understand in order to meet the needs of their Muslim constituents. The economy was among the top three policy concerns among 29% of Muslim respondents and 40% of members of the general Illinois public. After that was healthcare, which 20% of Muslim respondents and 19% of Illinois general public chose as a top concern. It is to be noted that 6% of Muslim respondents said that foreign policy was a big issue for them, as did 5% of Illinois general public respondents. Perhaps not surprisingly, 31% of Muslim respondents said that Islamophobia was a top issue for them, while only 1% of Illinois general public respondents rated it as one of their top concerns.

A bar graph showing top policy concerns cited by the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

NEED: Mosque Opposition Remains a Challenge

When comparing the experiences of Muslim faith groups with other faith groups in terms of creation of spaces of worship, more than one-third (39%) of respondents in the Muslim sample reported that their house of worship experienced significant resistance within their local community to move, build, or expand their mosque. Interestingly, a similar percentage of the general public reported the same challenge. However, the general public was more likely to not have a need to seek permission, with 46% of Illinois general public respondents stating that they did not seek approval from the city or zoning board, compared to 30% of the Muslim sample. This suggests that Muslims are not more likely than Illinois residents of other faiths to face city or zoning board resistance when building or expanding their house of worship but are also more likely to face the situation of needing to seek permission, perhaps due to a more rapidly growing community. This may present an opportunity for greater interfaith cooperation when faith communities are seeking to build or expand their houses of worship. To learn more about the resistance Muslim communities sometimes face when seeking to build or expand their house of worship, see ISPU’s report Countering Anti-Muslim Opposition to Mosque and Islamic Center Construction and Expansion.

A bar graph showing proportion of the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public who faced resistance to mosque opposition or building plans

NEED: Religious Discrimination

Muslim respondents reported significant religious discrimination from outside their faith community, which has repercussions ranging from public health, to employment, to political representation and needs to be an important focus for government and non-government organizations tasked with ensuring equal rights. While 52% of Muslim respondents stated they faced religious discrimination outside of their community, 24% of Illinois general public respondents said they have faced religious discrimination.

A bar graph showing frequency of religious discrimination by someone outside faith community among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

Discrimination poses a significant challenge to the Illinois Muslim community and was a consistent theme among focus group respondents, as noted in their policy priorities. There was quite a bit of variety within this theme, ranging from the most specific sort of discrimination directly targeted at Muslims, to discrimination directed toward immigrant communities or racial and ethnic groups that included Muslims, such as African Americans and, more specifically, African American Muslims. A less consistent but also present theme was discrimination within the Muslim community, particularly interethnic and interracial discrimination.

“In my view the greatest challenge is Islamophobia which is causing a security issue for Muslims. Being an Imam, we had to hire a security guy to protect us… It is hard for me when we have a security guy who is armed. He must be present at the door when people come to worship and it’s hard to see him when children come and they ask why he has to be here… Just to have him we feel insecure. When will we feel safe again to go back to normal?” – White male focus group participant

“Racism. Anti-black racism. Clear cut between African American Muslims and Muslims from South Asia. Family is from Sudan. We identify as black; we are African. Being in that space, I’m aware of the fault lines. Anti-black racism and racism in general: class division between aspiring middle class/upper class life in the US and the values connected to that. Lack of solidarity with working class people across racial and religious grounds. Biggest fault lines.” – African American focus group participant

NEED: Hate Crimes

Muslim respondents were just as likely as the Illinois general public respondents to be victims of hate crimes (9% vs. 10% respectively). These results point to the need for greater support for all vulnerable communities against bias-inspired crimes and an opportunity for coalition building.

NEED: Bullying

Forty-one percent of Illinois Muslim sample respondents stated they have a child between kindergarten and twelfth grade. Of those respondents with school-age children, 80% stated their child attends a public school, 10% attend a private non-Muslim school, and the remaining 11% attend a Muslim school.

Just as a significant portion of adults in the Illinois Muslim sample report facing discrimination, the children of Muslim respondents face bullying. Specifically, 29% of Muslim respondents who have a child in K-12 stated their child has experienced some form of bullying. By contrast, 49% of Illinois general public respondents with a child in K-12 stated their child has been bullied. It is worth noting that national data shows that 50% of Muslims have experienced religious-based bullying, as opposed to 27% of the general public [12]. Among Muslim respondents, 14% stated their children were bullied because of their race, 6% said national origin, and 9% said religion.

A bar graph showing frequency of bullying faced by children reported by parents of school-age children among the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

Finally, it was found that Muslim respondents’ children who were bullied were most often bullied by their own peers (68%) while 10% said a teacher did the bullying and 5% said the bullying was anonymous.

A bar graph showing reports of who has bullied their child among parents of school aged children in the Illinois Muslim sample and Illinois general public

NOTES

[7] https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/AMP-2016-12_Logo.png?x46312

[8] https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/AMP-2016-8_Logo.png?x46312

[9] https://news.gallup.com/poll/148931/presentation-muslim-americans-faith-freedom-future.aspx

[10] Population estimate for Illinois Muslims were based on findings from the Pew Research Center

[11] https://www.ispu.org/american-muslim-poll-2020-amid-pandemic-and-protest/#voting

[12] https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/AMP-2020_29_Logo.png?x46312